In 1950, Princess Eugenia Ruspoli, an American-born woman who became an Italian noble through marriage, donated Pietro da Cortona’s Triumph of David painting to Father Daniel P. Falvey of Villanova College as one of many artistic gifts to decorate the walls of the newly established Falvey Library. Throughout Princess Ruspoli’s life she was not only an art lover, but also a collector of rare, eloquent, religious paintings.[1] In fairytales, young women who marry princes live happily ever after, but Princess Ruspoli’s story was nothing of that sort. Princess Ruspoli’s family came from old money, and they were prestigious militarily and notorious politically. Eugenia’s prince chased after her, yet he likewise took advantage of her financially. Prince Ruspoli unexpectedly died in the prime of his life, and in his will ousted Eugenia from the majority of their marital property.[2] Princess Ruspoli had her wealth, fame, and share of legal woes, but one mystery about Eugenia remains – was it egoism or her Catholic faith that led her to give much of her prized art collection to churches, colleges, and museums during her lifetime?

The life of our philanthropist began on October 19, 1861 when Princess Ruspoli was born Jennie Enfield Berry to Frances Rhea (1838-1926) and Thomas Berry (1821-1887) on her family’s Turkey Town Plantation in Etowah County, Alabama.[3] The eldest of eight children, Jennie came from two socially-prominent family lines. Her mother was the daughter of affluent plantation owners in Alabama, while her Tennessee-born father was a first lieutenant in the Battalion of Georgia Mounted Volunteers during the Mexican-American War (1846-1848) and a captain in the Confederate Alabama Infantry during the Civil War (1861-1865).[4] To add more glory to her family’s name, Jennie Berry’s paternal grandfather, James Enfield Berry (1790-1857), was the first mayor of Chattanooga, Tennessee (the fourth largest city in Tennessee today) when he occupied the position for one year in December 1839.[5]

By 1870 Jennie Berry was documented in the U.S. Federal Census as living in Rome, Georgia on her family’s estate, Oak Hill. At this time, Berry’s father was a merchant who worked with a group of business partners (including two of his brothers) in Berrys and Company, an entity that functioned as a grocery wholesaler and buyer and seller of cotton. Berry’s family was so well-off that the family now lived in a Greek revival home with two live-in servants. Also, Berry’s mother held $1,000 in real estate while her father held $4,500 in real estate and had $15,000 in personal estate; in today’s figures, the Berry family’s total property wealth would be $372,000! Furthermore, Berry had a stable family life and throughout her youth her parents cultivated a cosmopolitan sensibility in Jennie by sending her to study in Europe.[6]

At the age of 27, Berry wed for the first time on May 7, 1889, to the Dublin-born tobacco manufacturer Henry Bruton, in Nashville, Tennessee.[7] Bruton was a partner in the American Snuff Manufacturing Company along with his brothers and businessman Martin J. Condon – until his death from “outer colitis” (simply put, an ulcerative colon) on December 5, 1892.[8] After Bruton’s death, Berry inherited millions and became an American socialite in her own right. By 1901, she had met the Italian noble Don Enrico Ruspoli, a 23-year-old prince associated with the Italian embassy in Washington, D.C. who came from a “financially poor” branch of the Roman Ruspoli family. Berry and Ruspoli parted ways, yet Ruspoli later followed her to Georgia to ask for her hand in marriage.[9] On March 2 of that same year, the couple was married by Monsignor Martinelli before the Nuncio of the Holy See in Washington, D.C., and Jennie became an Italian citizen and princess. The Ruspolis later moved to Italy and took up residence in Rome.[10]

By 1902, she solidified her status as a princess by changing her name and religious affiliation and by acquiring historic and artistic treasures. First, Jennie renamed herself “Eugenia,” which means “well-born” and is also the name of two famous Christian saints, Saint Eugenia of Rome (d. 258 AD) and Blessed Eugenia Smet (1825-1871). Second, she converted to Catholicism to coincide with the faith of her husband. And third, Princess Ruspoli bought from the Orsini family the 85-room, Castle of Nemi (located in the province of Rome, overlooking the famous lake of the same name) with her own funds, but the purchase was filed under Prince Ruspoli’s name.[11] After obtaining the castle, Princess Ruspoli collected several rare paintings created by Italian and Flemish Baroque artists including as Giambattista Pittoni (1687-1767) and Pieter Neeffs I (1578-1656).[12]

On December 4, 1909, Eugenia became a widow again when Prince Ruspoli died in Nemi Castle after suffering from a long-term, unknown illness.[13] Not long after the prince’s death, Princess Ruspoli learned that her husband had left most of their marital property, including the castle, to his siblings. Thus began a prolonged legal dispute over the castle where she resided and housed her art collection. The quarrel ended seven years later, at which time Eugenia was granted the castle she had originally bought with her own money.[14] By 1931, Eugenia regularly travelled from Italy to the United States and she maintained her own art salon in New York City. During that same year Ruspoli also began to donate her art collection, including what seems to be a sixteenth-century copy of Correggio’s altarpiece known as Il Giorno, or the Madonna of St. Jerome (originally for Parma’s church of Sant’Antonio Abate but now in the town’s Galleria Nazionale), which was granted to Father Joseph Cassidy of St. Mary’s Catholic Church in Rome, Georgia.[15]

By 1942, with World War II raging, Princess Ruspoli resided in the United States, having fled Italy under the fascist dictatorship of Benito Mussolini. She soon encountered further troubles when the Castle of Nemi was “requisitioned” by the Italian government and “turned over” to the German Luftwaffe. Her family would later claim that the Nazis looted and/or destroyed “over a million dollars in art treasures, paintings and the like and only five pictures were salvaged.” These paintings, with Pietro da Cortona’s canvas among them, were shipped to the U.S. once the war was over.[16] As late as 1949 (five years after the Germans vacated the structure), it was reported that sixteen, bombed-out refugee families were still living in the castle as squatters. Even though Princess Ruspoli was never absolutely certain who extensively damaged the castle, she went after the Italian government for over $1,000,000 in compensation for her war-torn castle.[17]

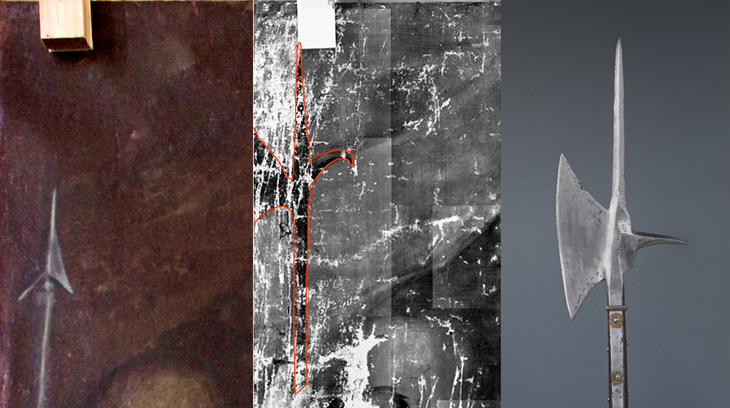

Despite the various legal disputes troubling Eugenia Ruspoli late in her life, she continued to donate her art treasures. In 1949, she granted two paintings to Villanova University, and in the following year additional works, including Pietro da Cortona’s Triumph of David.[18] On the night of January 26, 1951 – at the age of 89 – Princess Ruspoli died in her New York City apartment. Before her death, she wanted to continue giving, and she planned, once pending litigation was settled, to donate the Castle of Nemi to the Holy See, to be used as an American-Italian educational center.[19] A few years later, in memory of the generous Eugenia, her family her family paid $900 ($7,600 in today’s figures) for the framing and conservation of Pietro da Cortona’s The Triumph of David, and they and donated additional early modern European paintings to Villanova.[20] In the end, no one knows exactly why Princess Ruspoli gave Villanova so many valuable artworks. Historians are currently not aware of any journals or letters she authored that may provide insight into her motives for making charitable donations to the university. Therefore, the reader of her tale must weigh, did Eugenia donate those paintings just to receive accolades from local newspapers and her peers, or did Ruspoli give them away in her old age to educate young college students? Overall, it can safely be said that Princess Ruspoli, a millionaire and a Catholic convert, chose to donate her collection because she did not need it financially, and she wanted a Catholic educational institution to treasure the religious paintings as she once did.

By Menika Dirkson

[1] Rita H. DeLorme, “The princess, a painting and a Georgia Church,” Southern Cross, (Dec. 22, 2011): 5, accessed, Oct 22 03:35 EDT 2013, diosav.org/sites/all/files/…/A%2012-22-2011%20CROSS%205.pdf.

[3] “Biography: Eugenia Ruspoli; Italian Countess,” Berry College Memorial Library, August 29 2013, accessed Oct 22 02:16 EDT 2013, http://libguides.berry.edu/content.php?pid=426504&sid=3489581.

[4] “Biography: Capt. Thomas Berry (1821-1887): Soldier, Farmer and Merchant, Father of Martha Berry,” Berry College Memorial Library, January 23 2014, accessed Oct 22 02:16 EDT 2013, http://libguides.berry.edu/content.php?pid=426504&sid=3489581.[3] “Biography: Eugenia Ruspoli; Italian Countess,” Berry College Memorial Library, August 29 2013, accessed Oct 22 02:16 EDT 2013, http://libguides.berry.edu/content.php?pid=426504&sid=3489581.

[5] “Biography: James Enfield Berry (1790-1857): First Mayor of Chattanooga,” Berry College Memorial Library, January 23, 2013, accessed Oct 22 02:16 EDT 2013, http://libguides.berry.edu/content.php?pid=426504&sid=3489581.

[6] Washington, D.C., National Archives, U.S. Census Bureau, 1870 US Census, accessed January 22, 2014, http://www.ancestry.com.

[7] “Biography: Eugenia Ruspoli; Italian Countess.”

[8] Ancestry.com, Tennessee, City Death Records, 1872-1923 [database on-line], Provo, UT, USA, accessed January 23 2014, ancestry.com

[11] “Biography: Eugenia Ruspoli; Italian Countess.”

[12] George T. Radan and Richard G. Cannuli, Villanova University Art Collection: A Guide, Villanova: Villanova University, 1986.

[13] Mary Alsop King Waddington, Italian Letter’s of a Diplomat’s Wife, January-May, 1880, February-April, 1904, New York City: C. Scribner’s sons, 1905.

[14] “Biography: Eugenia Ruspoli; Italian Countess.”

[15] DeLorme, “The princess, a painting and a Georgia Church.”

[16] Sanford Schnier, “Caught in Italian Red Tape: Russian Prince Wants His Castle Returned,” The Miami News, (Oct 27, 1957): 15A , accessed, Jan. 23 2014 15:14 EDT, http://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=2206&dat=19571027&id=EJQzAAAAIBAJ&sjid=neoFAAAAIBAJ&pg=2376,4592300.

[17] George Bria, “Castle Squatters a Problem for Italian Government,” St Petersburg Times, (Dec. 13, 1949):18, accessed, Jan. 23 2014 14:57 EDT, http://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=888&dat=19491213&id=NBxPAAAAIBAJ&sjid=ek4DAAAAIBAJ&pg=5011,2097931.

[18] Radan and Cannuli, Villanova University Art Collection, 39.

[19] “Deaths Elsewhere: Italian Princess Dies in New York,” The Miami News (Jan. 27, 1951):7A,accessed, Jan. 23 2014 15:44 EDT, http://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=2206&dat=19510127&id=F6IyAAAAIBAJ&sjid=IewFAAAAIBAJ&pg=4820,6538404.

[20] “McClees Galleries Frame Receipt June 26 1956,” Ardmore: McClees Galleries, 1956.